Accueil > Voir, Lire & écrire > Lire & écrire > Parched : The Art of Water in the South West

Parched : The Art of Water in the South West

At the Coconino Center for the Arts, Flagstaff, Arizona September 11, 2020 to January 9, 2021

,

Parched : The Art of Water in the South West is a group exhibition curated by Julie Comnick at Coconino Center for the Arts in Flagstaff. The exhibition brings together nine visual artists from Arizona to explore, learn, and reflect water issues in the region.

The artists spent a week together, participating in what the curator calls “the Boot Camp” to visit places in Arizona, such as Gray Mountain, Glen Canyon Dam, Navajo Generating Station, and Tuba City. During that time, the artists learned from scientists, policymakers, and conservationists about the ecosystems of local water, water management, and the biogeography of the Colorado River, and other topics related to water.

The nine artists in the exhibition interpreted what they learned from “the Boot Camp”, using various artistic media. One of the pieces that stand out the most is a video piece titled Saurian Memory by Delisa Myles. It was video documentation of a choreographer, dancing poetically inside another large-scale installation piece in the same exhibition titled The Bodies Gone, the Purchases Made created by Shawn Skabelund. In other words, Myles performed her dance out of Skabelund’s sculpture. Skabelund and Myles collaborated on their pieces for Myles’ performance. However, the final works are presented as separate pieces. The material that fills Myles’ installation is a cattail down. Cattails are upright perennial plants with long tapering leaves that have soft edges and are moderately spongy. A group of participants spent several hours popping open cattail pods to cover Myles in the sculptural installation. For Skabelund, the cattail down is a metaphor of snow made from effluent water (treated sewage) and the controversy of using reclaimed wastewater for snowmaking at the Snow Bowl ski area on the San Francisco Peaks. The San Francisco Peaks are a volcanic mountain range in north-central Arizona near Flagstaff. The mountain has been a sacred place for the Hopi and other Indigenous people. Myles claimed that the choreographer in the video is a mythological creature called "Serpent River Woman," who is a guardian of water and protector of portals between earthly and spiritual realms. The choreographer speculated what it would be like to be in a post-apocalyptic world in the time after the great droughts, famines, fires, and floods and expressed them through beautifully choreographed bodily movements. The Skabelund’s large-scale circular installation filled with the cattail down is reminiscent of a post-apocalyptic world full of calm white ashes.

Speaking of a post-apocalyptic world where all lives are gone, Neal Galloway’s sculpture titled Ground Water added another comment on this dark speculative future. He presents an object that looks like an ancient Buddhist’s fountain that we expect to see water flowing from the top. However, instead of water, the fountain is filled with sand. Right next to this sculpture, a video shows the sand on the fountain falling down, just like the sand in an hourglass. This suggests a speculative future of extreme droughts where no water remains, but the sand flow like water. In the exhibition catalog, Galloway explains that “Ground Water imagines a future in which the environmental reality of water catches up with our antiquated and short-sighted attitudes, habits, and laws.” Galloway asks the viewers to review the forms of our modern life and re-think about what we need to do for a more promising ecology in order to avoid the arid landscape full of sand.

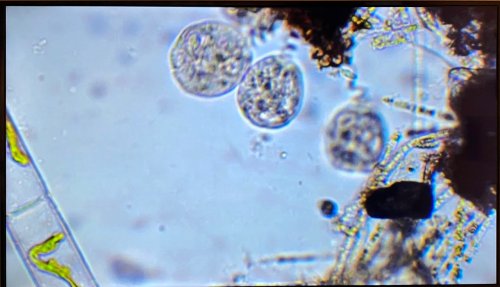

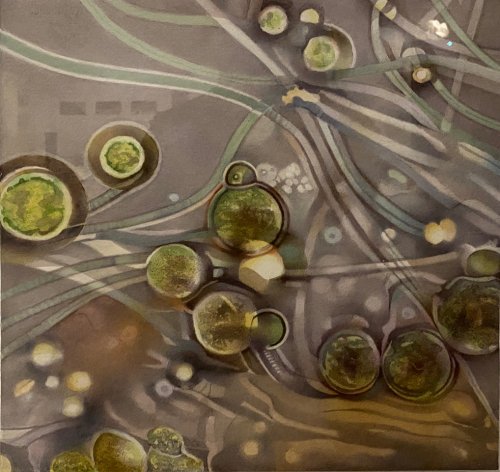

Another work that I found interesting is Debra Edgerton’s series of drawings and video titled Life Extended. Recently, scientists discovered that certain types of bacteria live in extremely hot and cold places where we formerly thought impossible environments for living creatures. However, some microorganisms can survive in boiling water and in the frozen area. For example, a microbe has been discovered in the high Canadian Arctic at the coldest temperature known for bacterial growth. This suggests that hostile planets for life, such as Mars, can host some of Earth’s toughest microbes to survive. Edgerton filmed the microscopic world from the water she collected from Fossil Creek, using a microscope. In the video, the audience can see unknown microscopic organisms moving around. We are not able to see these microscopic organisms with our naked eyes. That doesn’t mean life doesn’t exist. These small organisms are hidden from our normal sight but play very important roles in the ecosystem in which we live. Edgerton created a series of abstract watercolor paintings based on the microscopic images she captured. In the catalog, the artist claims that “For more than 100 years, water from the Verde River and Fossil Creek has been diverted to the power plants at Childs and Irving hydroelectric facilities. However, conservation organizations convinced APS that the restoration of Fossil Creek’s ecosystem would have a far greater benefit than the continued production at the power plants. In 2005, APS stopped diverting water to these plants to let water once again flow freely through Fossil Creek.” Her paintings present the growth of algae in the reclaimed ecosystem at Fossil Creek.

The Healing Dance at Hooghan (Home) is a video piece created by Marie Gladue. In the video, a group of indigenous people dancing together in nature. It portrays the struggle of the Dineh (Navajo) community at Big Mountain due to the relocation issues. Many of them live without direct access to water to their homes as they are dealing with increasing drought and hauling water. The state wants to divert water from the Little Colorado River to the cities like Phoenix and Tucson, while the indigenous community strives to negotiate for the land they want to stay. The dance in the video represents their wish to heal the land, water, air, and people. The artist asks us a sustainable future for the indigenous people.

This carefully curated exhibition asks us why water matters. As industrialization has continued to allow businesses and large corporations to expand, the environment has been negatively impacted by the increase in water pollution, consumption of natural resources, and development of cities. Contemporary art plays a crucial role in activist efforts to inform people about the importance of reducing humankind’s impact on nature. The exhibition presents our intricate inter-relationship with water through diverse perspectives and provides us time to contemplate the various water issues in Arizona. The exhibition is especially meaningful for local people who care about the future of Arizona’s ecosystem in the age of climate change.

*The cover image is taken by Matt Beaty